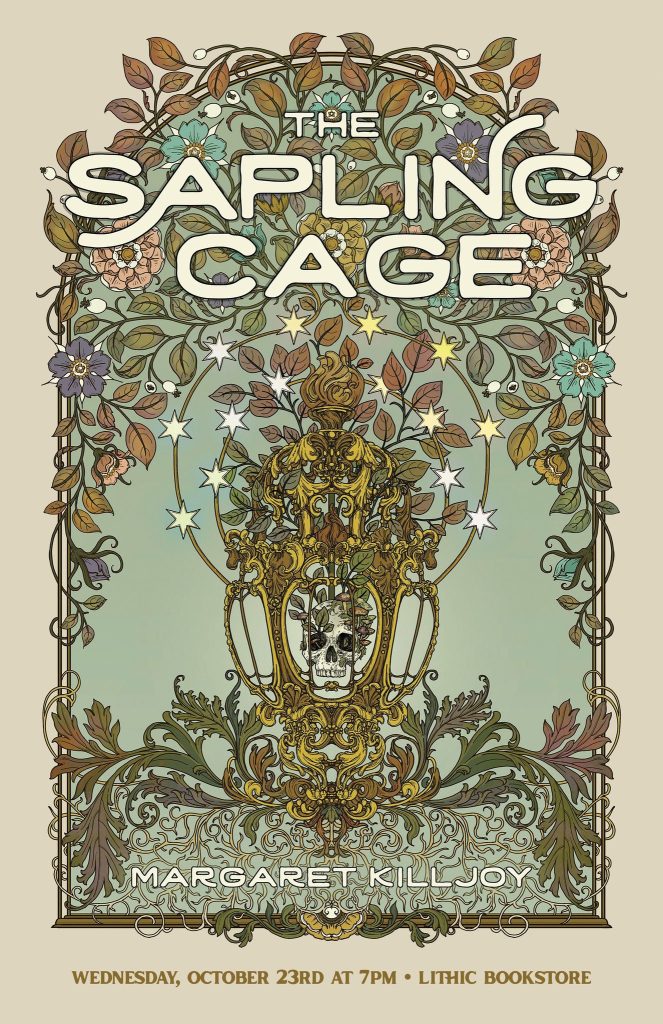

Margaret Killjoy will be reading from her newest book The Sapling Cage at Lithic Books in Fruita. Wednesday, October 23 at 7pm.

The Revolutionist: You have so many creative projects. We are in awe. Between your music, podcasting and your writing, what keeps you motivated. What moves you to create?

Margaret Killjoy: Oh, it’s what gets me up in the morning, it’s what keeps me going. I used to create because I felt like I didn’t have any other good way to connect with people, if I’m being honest, but these days it’s just what I enjoy the most. I like spending most of my time making things (by myself or with others) or plotting out making things. I don’t like parties very much, most of the time, but I sure love getting a bunch of people together and brainstorming strange things.

I also write to try to have my hand in the collective shaping of the world, and I’m really blessed to get to be doing that—I think all of us are.

TR: Your newest book, The Sapling Cage has been billed as “a tale of trans witchcraft, found family, and resistance against corrupt authority” Can you speak to the power of fantasy and fiction in challenging social norms and power structures?

MK: So, a lot of fiction, including a lot of my own fiction, exists to challenge social norms, for sure. It’s good at that task, because it allows us to understand emotionally, not just intellectually, what is wrong with this or that way of doing things. But lately, what I’m most excited about is fiction’s ability to not just critique the existent, and not just imagine better alternatives, but to just show that this shit could be different. Fiction helps us understand that not everyone thinks like us, that not everyone lives in the same sort of world as us. I love writing fiction where people just operate on entirely different (not necessarily better or worse) ethical frameworks than we do. I think that is inherently radical, because, well, we’re all told that the way things are is the way things must be. But if we can imagine ourselves moving through a different society (again, not even necessarily a better one), we can realize… oh, humans can operate in a lot of ways.

Of course, nonfiction can do this too, like the book The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow, but I say we should attack the hegemony of the existent from every angle we can.

TR: How did you come up with this story line? How long have you been working on this?

MK: I wrote The Sapling Cage in probably 2016 or 2017, coming off the heels of writing the first two Danielle Cain Books. I couldn’t tell you exactly when I hit upon the basic idea, of a young person dressing up as a girl to go join the witches, but it was probably a bit before then … I only came out as trans in 2016 myself, and I wanted a way to really start looking at what that meant to me, a way to start talking about it.

TR: The first book of yours that we remember is Mythmakers and Lawbreakers, a collection of interviews you did with anarchist writers of fiction, how did that project influence your fiction writing? We can’t imagine meeting Ursula K Le Guin and walking away unchanged.

MK: I used to see my fiction writing and my political work as two separate things. Fiction was a hobby, organizing anarchistically for a better world was my full-time profession (well, it didn’t pay, but it’s what I did). Le Guin was the first author I talked to for that project, and in that simple short email she did something really basic and important: she explained to me that it was okay to have fiction be what you do, so long as you don’t use that as an excuse to get out of the grunt work. She was glad anarchists left her alone to her writing and didn’t expect her to organize but would still march in any anti-war march and would stuff envelopes for Planned Parenthood. We all naturally specialize, even us jack-of-all-trades types, but we should still do some generalist work from time to time. That’s how I interpreted it, anyway.

So, I started taking my fiction writing more seriously, which I’m glad for. I don’t hate the stuff I wrote back then, but it was shortly after that when I started well, getting good at it.

TR: You also have two podcasts? Can you tell us about those?

MK: You there, the reader. The person reading this. If you have stable housing, do you have three days of water, food, and cell phone battery life stored up? If you don’t, you should.

I run a podcast called Live Like the World is Dying, which I started in 2020 about a month before the pandemic hit, and it was my attempt to bully my friends into becoming preppers, and to bully the preppers into becoming more community minded. It’s still around, but I’m no longer the only host… there’s a rotating cast of us, and we discuss everything from gardening to antifascist organizing. Comes out every Friday.

My day job is a different podcast, Cool People Who Did Cool Stuff.

TR: I find your history podcast, Cool People Who Did Cool Stuff, fascinating! We try to cover our local radical history. Why is digging into suppressed history so important?

MK: Okay I clearly love narrative, right? Well, it turns out we’re all part of the grandest story ever told, the story of the world. We’re characters in that. We have agency. But the way that history is generally told, folks like you and I don’t have much agency. It’s just a few random rich people, or rarer working-class people, who do anything in the mainstream histories we read. But that’s simply not true. History is made by each of us. And the contributions of so many people are regularly left out. Women are left out, constantly. The queer status of people is left out. And anarchists? Left out. If you read mainstream leftist theory, it’s just communists with a smattering of social democrats or whatever. Anarchists—and antiauthoritarians more broadly—have been a major part of so many histories, so many revolutions, so many cultures. And you have to dig to find it, because yeah, if someone is an anarchist, that’s somehow left off their bio unless they threw a bomb at this or that political figure.

Take the history of fiction… Ursula le Guin of course, but also Tolstoy. There’s this entire huge, influential lineage that descends from Tolstoy’s Christian Anarchism. Oscar Wilde…. famous as a playwright and a witty gay man, but he wrote one of the better and most widely-read anarchist socialist tracts of the 19th century, one that gets into everything we’re talking about now… it’s called The Soul of Man Under Socialism and in it he argues that the point of art isn’t to make socialism, the point of socialism is to enable us to make art. He also like, bailed anarchists out of jail. The Modern Library wrote a list of the 100 best novels of the 20th century. Three of the top 5 were written by anarchists… James Joyce wrote two and Aldous Huxley another. Yet no one teaches those Big Important Famous Literary Men as anarchists. An interviewer once asked Henry Miller “you call yourself an anarchist, yet you’re so organized…” and Henry Miller was like “yeah.” And the interviewer was all flustered, clearly not understanding anarchism, and was like “well why do you call yourself an anarchist?” and Henry Miller was like “because I like read Kropotkin and shit, what the fuck.” (I paraphrase from memory here).

The world’s first modern pop star, Charlie Chaplin? Not exactly the best feminist, but he was an anarchist.

Anarchists have been the arts, disproportionately represented, forever, but our politics are systematically stripped from our legacies.