by The People’s History of the Grand Valley

On April 7, The Supreme Court approved Trump’s invocation of the Enemy Aliens

Act to deport migrants. On April 28, Trump signed an executive order titled “Strengthening and Unleashing America’s Law Enforcement to Pursue Criminals and Protect Innocent Citizens.” Which federalizes local law enforcement, protects law enforcement officers from civil rights oversight, and indemnifies officers from any wrongdoing in the course of their duties, it additionally seeks to use the military in domestic law enforcement. Many rightfully fear this order is martial law by a different name. These are real fears, and these are unprecedented times, but there are some lessons from local history that can help us navigate these troubled waters and hopefully inspire resistance to federal repression in the future.

Martial Law in Grand Junction?

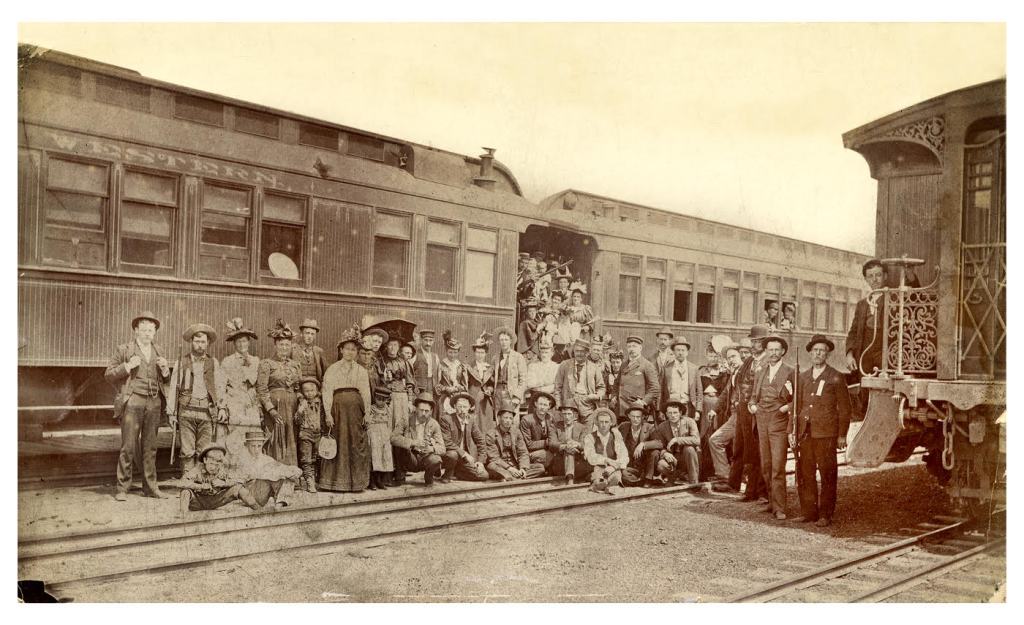

I n 1894, one of the most consequential labor strikes in U.S. history brought the nation’s railroads to a halt. Grand Junction railroad workers were largely organized into Eugene Debs’s American Railway Union. In late June of 1894, the ARU voted to boycott, not work any train with pullman sleeper cars, in support of an ongoing wildcat strike at Pullman’s company town named (appropriate enough) Pullman, Illinois.

Grand Junction workers enthusiastically halted work in solidarity with workers at Pullman. President Cleveland invoked the Insurrection Act to quell the strike through force; some 80 strikers and sympathizers would be murdered by the state across the country.

Quickly, U.S. Marshals deputized and armed 600 men from the streets of Denver. America was in a depression far worse than the Great Depression, which ironically enough was started by a trade war of ever-escalating tariffs. The U.S. Marshals and their newly deputized thugs set off to squash the strike in every rail junction between Denver and Ogden, Utah. The citizens of Ogden had captured a number of trains, setting up camp in front of and in the rear to keep the trains from moving.

The strike breakers first encountered trouble in Glenwood Springs where workers had dynamited 100 yards of tracks. They rebuilt the tracks quickly, many of the newly deputized

Marshals being unemployed railroad men.

In New Castle, a man was arrested for attempting to burn down the railroad bridge into town. New Castle was a coal mining town that was heavily unionized by the militant Western Federation of Mine Workers. Additionally, the main switch in the New Castle train yard had been sabotaged.

A few miles west of New Castle, a small bridge over a dry gully was packed with firewood and set ablaze.

Eventually the train arrived in Grand Junction a few days behind schedule. The citizens

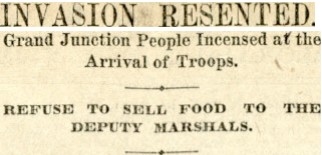

of Grand Junction knew the train was coming, and the Populist Party, the ARU and citizens standing in solidarity held a mass meeting in a park and made a plan for how our community would resist. U.S. Marshal Joseph Israel reported back to his superiors in Washington that:

“The conditions of affairs at Grand Junction were extraordinary, my deputies were met

not only by the strikers at that point but by the citizens who met in a public hall prior to

their arrival and resolved to not only resist the entry of the deputies to the town, but also

to give them no quarters or sell them anything to eat!”

The Marshals backed the train up to Palisade for provisions, and in the middle of the night re-entered Grand Junction. They took possession of the railyard and arrested nine leaders of the strike, sending them to Denver via train in secret.

Grand Junction woke up, on July 4,1894, to martial law. A few days later, federal troops would arrive against the protests of Grand Junctionites.

While still under martial law, local Populist Party activist and poet Jacob Huff

published a poem in the Grand Valley Star Times entitled “Stand Up Americans.”

Here’s just one stanza:

“This is no time for prejudice, no time to fight

Over politics or public men;

Stand shoulder to shoulder, each man for the right,

and shout this o’er valley and glen;

‘Tis the land which our fathers have died to make free

From the grasp of old England’s crown;

If we stand up like men for our own liberty,

They dare not shoot the lab’ring man down.”

WWI and the Rise of the Super Patriot

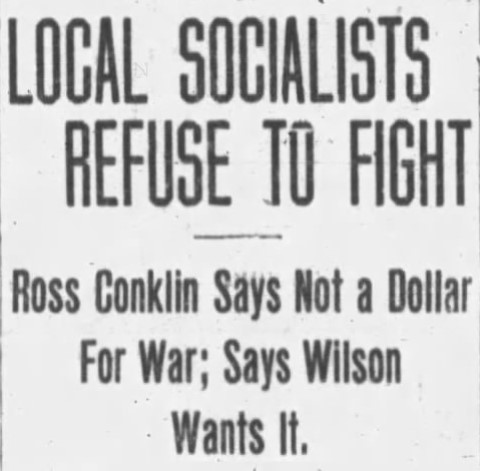

World War One was not a popular war, and to squash dissent, Woodrow Wilson invoked the Enemy Aliens Act to deport foreign born critics of the war, and leftist radicals. Wilson also passed the Sedition Act which criminalized anti-war speech. The act was used to squash

dissent, locking up writers, publishers and orators.

Locally a Home Guard, which was organized ostensibly to fill the role of the Colorado National Guard which had been deployed to Europe, ran amok. Some 400 men in Mesa County were under arms in this quasi-official militia.

The Home Guard harassed socialists and persons of German and Austrian descent, spread fear about the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) and even ran I.W.W. farm workers out of Palisade at gunpoint. They burned Jehova’s Witnesses’ books for their non-cooperation with militarism and the draft; they arrested German immigrants for disloyal utterances and threatened citizens that were not significantly patriotic enough. In addition, the Home Guard intimidated the local socialist paper, The New Critic, into cessation of publication after they published an anti-war piece entitled “To Feed the Flies!” which ends:

“Multiply it by the fifty men who were taken, then think of it.

Multiply it again–by the thousands of cities over the nation where the same

black tragedy is being enacted.

What a huge toll of human misery.

For many can never return. They will leave their rotting bodies on the fields of France–to make the world safe for democracy. (And they say there is a God who punishes blasphemy.)

To make the world safe for democracy, NO! To make the world safe for the money lender.

To feed the files!”

The article was published the same week that fifty draftees from Grand Junction boarded a train destined eventually for the horrors of trench warfare in Europe. L. Ross Conklin, the editor, got the message. He never put out another issue of The New Critic, but he did publish one last circular about free speech. In Colorado Springs, the Home Guard burned down the socialist newspaper’s headquarters. Walter Walker’s Daily Sentinel was very much in support of the Home Guard and the shuttering of his competition, as well as their other extrajudicial activities.

Yet people still resisted. The Home Guard was openly heckled in Home Guard in Fruita in 1917. Some horses belonging to the Home Guard were stolen in Grand Junction while the Guards drilled in Whitman Park in 1918.

People regularly failed to register for the draft and failed to induct when drafted.

Around the nation and here in GJ, vigilante groups were funded and encouraged at the highest levels. Locally, Walter Walker, through the pages of The Daily Sentinel, was cheerleading the witch hunts by the Loyalty League who terrorized leftists, immigrants, and anyone not displaying appropriate amounts of patriotic fervor while publishing calls for citizens to spy on and report their neighbors to federal and local law enforcement by the American Defense Society. The ADS was a semi-official national spy/vigilante group, and in these calls to action, suspicious people were to be categorized as: 1) Enemy Alien, 2) Pro-German, or 3) Anti-government.

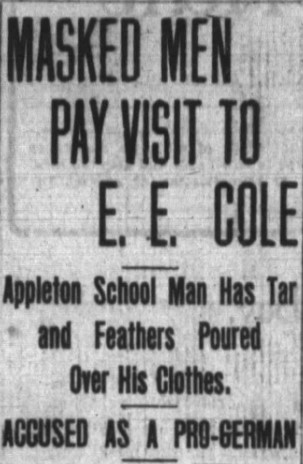

The superintendent of the Appleton school, E. E. Cole, was tarred and feathered by masked men with the Loyalty League in April of 1918. Also in April of 1918, the Montrose Daily Press reported that, M.O. Douglas, a Clifton farmer, had his house painted yellow (a sign of cowardice or lack of patriotism), was threatened with lynching and “forced to change his attitude, swear his allegiance to the United States, promised to support the president, and [buy] a Liberty Bond.” It was alleged that Douglas had made “disloyal statements for some time.”

The anti-war stance of the socialists and the I.W.W, and the heavy-handed response by the Wilson administration coupled with the local vigilantes he empowered effectively destroyed both the socialist party in America and the Wobblies, both of which are just shadows of their progressive-era strength today.

Many socialists in the west, those that didn’t join the Communist Party(s), re-branded into a short-lived “Non-Partisan League.” But by 1921, the NPL was all but dead, but not the people nor their ideas. A few years later in 1924, former socialists, union members, and farmers were organizing around Robert M. La Follette, the Farmer-Labor candidate for President. La Follette garnered a respectable 27.28% of the Mesa County presidential vote. By the early 1930s, Mesa County would again have a socialist party fielding a full ticket of candidates.

Despite the repressions, somehow socialism survived in Grand Junction.

At the same time Junctionites were resisting federal tyranny and vigilantes at home, former Junctionites around the country were also resisting.

Carl Gleeser, an early settler of the Grand Valley, a local labor organizer, a radical feminist, and avowed anarchist was publishing a German language, socialist newspaper in Kansas City, MO. Despite the risks, he published seven anti-war/anti-draft articles by Jacob Frohrwerk and was sentenced to 5 years in Leavenworth Federal Prison. Some 1800 people would eventually be imprisoned for speaking out against the slaughter.

George Falconer owned a radical bookstore in Grand Junction from 1901-1910. He was a thoughtful radical that made a name for himself as both a socialist and Wobblie but also as a man of letters, arts and refinement. After leaving Grand Junction, Falconer threw himself into the revolution. He reported on the Colorado Coal Wars of 1913-14. He spoke at Wobblie Joe

Hill’s funeral after he was set up by and executed by the state of Utah. Falconer would go on to be a founding member of both of the early American Communist Parties.

In late 1919 and early 1920, the Palmer raids targeted foreign-born radicals, including naturalized citizens, and many were deported with no due process to countries they had never lived in. According to the biography by Granville Hicks, “John Reed: the Making of a Revolutionary,” during this time of extreme repression of radicals, Falconer was passing messages between John Reed and Big Bill Haywood, along with other revolutionaries forced

underground.

Blacklisted communist writer, Dalton Trumbo, in his 1935 novel “Eclipse,” which was set in a

thinly veiled Grand Junction, explained how today’s repressions are but an echo or symptom of the repression unleashed during WWI:

“You formed a Loyalty League. Remember…They tarred and feathered old Professor Fuchs. That Loyalty League did something to this town… something that will never be overcome… For the first time Art French (Sterling D Lacy), and Walter Goode (D.B. Wright) and Stanley Brown (Walter Walker), and William Harwood (George Parsons) discovered that you were participating in the history of nations. Power—that was it…the power of snoopery, persecution, investigation. And no one dared oppose the snoopery and persecution, because no one dared risk the charge of treason… You can remember that not so long ago the Ku Klux Klan marched down main street at night, all ghostly with a fiery cross, an American flag and a drum. It was still the Loyalty League…the organized mob risen from its grave to snoop and tyrannize once more. And it will come up again and again, forever and ever! If there isn’t a good cause like a war, then it will parade for a poor cause. It will always be a cause with ideals so high that no mere law can restrain the execution of its judgments. And it will always be based on hatred and fear. Tomorrow it may come again… who knows?”

WWII Grand Junction as Refuge; and Then Not So Much

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt invoked the Enemy Aliens Act and issued executive order #9066 to detain Japanese immigrants and American-born citizens of Japanese descent, specifically, those living on America’s Pacific coast. There was a brief window of time from March 2, 1942, through April 1 of 1942 wherein

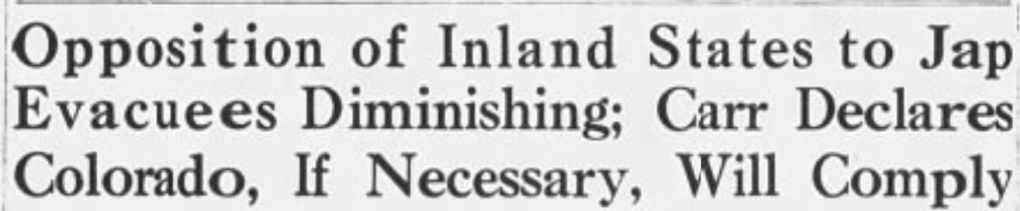

Japanese Americans could ‘voluntarily evacuate’ to the country’s interior. Most western states were openly hostile to the resettlement of Japanese Americans in their states.

Colorado, through Governor Ralph Carr, welcomed Japanese Americans to resettle in Colorado. Most major newspapers lambasted Carr’s approval of Japanese Americans resettling in Colorado, buy The Daily Sentinel had no reaction to the news and published a statement by the Chamber of Commerce that said that the Grand Junction business and farming community had no major objection to Japanese Americans resettling in the Grand Valley.

Just days after the voluntary evacuation period was over, Mesa County Sheriff H.E. Decker told The Daily Sentinel that his office had received several requests for Japanese farm hands, and that his department had “been turning over requests to representative Japanese families

in the county at whose homes a number of the evacuees from California are staying.”

Manabi Hirasaki, in his memoir, “A Taste for Strawberries,” describes coming here with his white farm manager, purchasing land near Fruita, and then rushing back to California to pick up his family—getting them here to safety just before the deadline. Hirasaki explained:

“We were open to Colorado because we had heard about its Governor Ralph Carr. He

publicly welcomed Japanese Americans to come….We ended up in Grand Junction, located on the Western Slope, west of the Rockies, not too far from the Utah border.”

Japanese internment camps were set up around the west, including Camp Amache near Grenada, Colorado. From these camps came a trickle of Japanese families that had passed a background investigation and were granted ‘permanent furlough’ and resettled in the

Grand Valley.

Many more came to Grand Junction under armed guard from Amache for the harvests and other labor-intensive seasonal tasks. Many were U.S. citizens and were incensed that

German POWs had free movement around the community unguarded.

In January of 1944, J.H. Lewis, Relocation Coordinator for western Colorado, was quoted by The Daily Sentinel, stating that there were fourteen Japanese families in Grand Junction before ‘voluntary evacuation.’ Eighteen families resettled as ‘evacuees,’ and additionally

twenty-four families had been relocated permanently to Mesa County from the internment

camps.

Lewis was speaking at one of many mass meetings being held by reactionaries throughout the Grand Valley and the state. The Elks initially adopted a resolution supporting legislation to bar Japanese Americans from purchasing land in Colorado. The Grand Junction City Council then adopted the Elks resolution, as did the Mesa County Commissioners, Lions

Club’s, and most unions. Lewis told the meeting and was quoted by the Sentinel that he was only aware of six purchases of land by Japanese refugees in Mesa County. Racial tensions continued to simmer through 1944 and into 1945.

A cross burning on the ridge above Orchard Mesa in October of 1945 was likely a

reminder for those refugees still in the Grand Valley that it was time to leave.

Paul Shinoda, another voluntary evacuee who fled initially to Idaho before resettling in Grand Junction, was happy to leave. He buried his father here. His wife and kids were arrested while ice skating on the Gunnison River near the then secret Manhattan Project uranium procurement operation that is now the Department of Energy, and he left as soon as he could. In an oral history, he stated:

“if they just picked the Japanese for an evacuation again… I’d raise holy hell and I’d sit here until they pretty well shot me before I’d move.”

Dalton Trumbo and McCarthyism

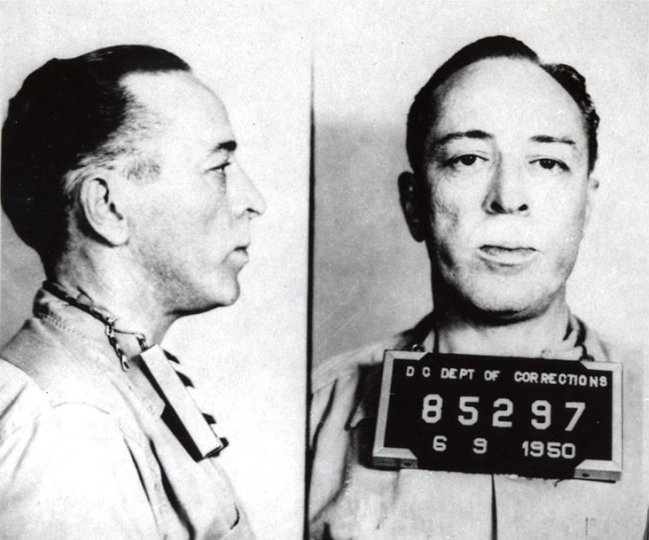

Dalton Trumbo was born in Montrose and raised in Grand Junction and is by all measures the most famous person the Grand Valley has produced. He published a poem in The Daily Sentinel at age 12, and by his late teens he was working as a cub reporter for the Sentinel. He published a few novels, famously Johnny Got His Gun, an anti-war classic and National Book Award winner, but he really made a name for himself as a screenwriter in Hollywood.

Then in 1948, Trumbo and his comrades were brought in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee in an effort to root out leftists—specifically communists and socialists—in Hollywood. They were asked the infamous question: “Are you now or have you ever been a communist?” And instead of cooperating, or pleading the fifth, they chose to plead the first: to talk back, to ask questions of their interrogators, to decry a purity test in a country that supposedly supports free speech. They became known as the Hollywood 10, and they each

spent a year in federal prison for contempt of congress and then returned to Hollywood only to find that they were ‘blacklisted.’

They found ways to work under fake names and for less money. Two of Trumbo’s screenplays even won Academy Awards for Best Story while being written under pseudonyms. Twelve years later in 1960, Dalton Trumbo would again be openly credited for his work on two films, Exodus, and fittingly, Spartacus. Finally breaking the blacklist.

The Red Scare, as it became known, touched more than just the lives of academics, government employees, and Hollywood, but Trumbo, a Junctionite, is still very much the

poster child of resistance to it.

Of Drafts and Bombs: Vietnam War Era

Forcing young people to go and fight in foreign wars is never very popular, at least not amongst those being drafted, or those whose husbands, fathers and boyfriends could be drafted.

A local resistance began to build starting in 1968, including veterans returning from Vietnam using their GI Bill benefits to attend college. There were protests on campus largely centered around the bell tower as well as teach-ins. Black armbands were worn at Fruita High School after the Kent State shooting.

Tillman Bishop, a longtime local politician was then head of the local draft board. On November 22, 1969, his home office was burglarized, and the local draft boards’ records were burned in the yard. Numerous young men resisted the draft; they failed to register, they failed to induct, they fought prolonged court battles winning their appeal after the local draft board misrepresented what conscientious objector meant, and others fled and sought asylum in Canada and Sweden. Non-cooperation is resistance.

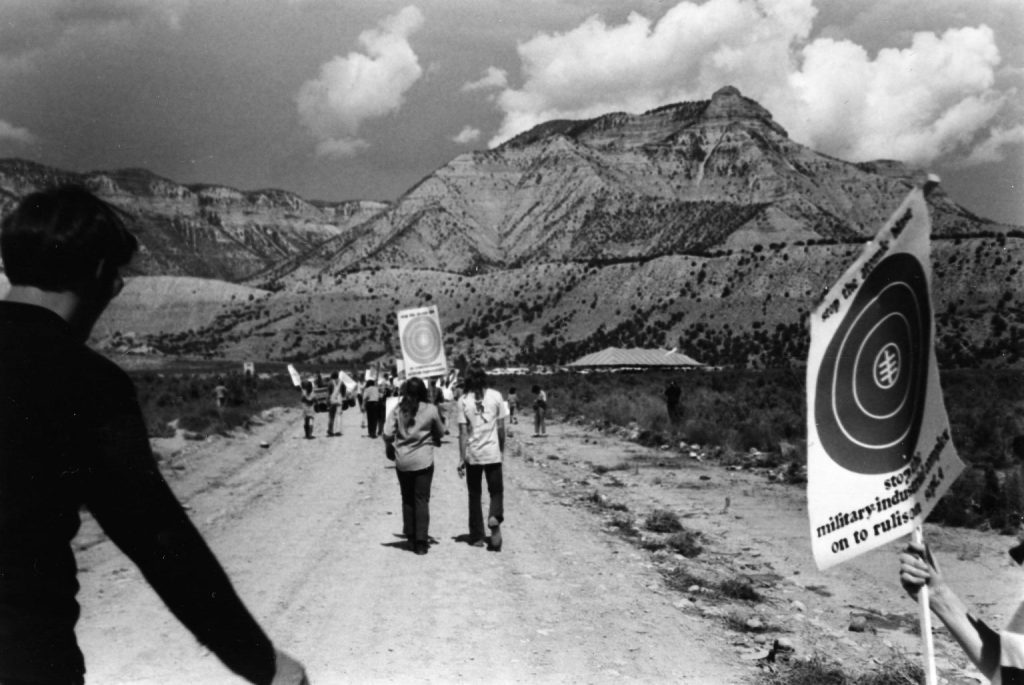

In 1969, the Atomic Energy Commission, in a quixotic attempt to find domestic uses for nuclear bombs, decided to go forward with Project Rulison. Project Rulison was a crude, and ultimately unproductively radioactive attempt at fracking for natural gas just outside of Parachute, Colorado.

Though the government had given the project the green-light, activists had other plans. Chester McQueary wrote in High Country News about his experience at ground zero:

“On Wednesday, Sept. 10, the go-ahead was given, and we scattered over the mountain in twos and threes, so that we could not all be removed in one fell swoop by authorities. We listened on portable radios to the countdown for the blast being broadcast on Rifle’s KWSR.

At 30 minutes before blast time, we set off smoke flares to confirm for AEC officials that we were still on the mountain and inside the quarantine zone. A blue, twin-rotor Air Force helicopter soon hovered 50 feet above the aspen clearing where Margaret Puls and I stood. Men in the open door gestured and shouted inaudibly at us. They could not land on the steep slope safely, and we had no intention of being passively taken off the mountain so the AEC could then claim that they had lived up to their word regarding a human-free quarantine zone. Since they’d known of our presence on the mountain for nearly a week, we wondered if some sort of special forces might suddenly slide down ropes from the helicopter door.”

McQueary further describes the 40 kiloton nuclear blast: “Then a mighty WHUMP! and a long rumble moved through the earth, lifting us eight inches or more in the air. We felt aftershocks as we lay there looking at each other, grateful that we were still breathing and all in one piece.”

Takeaways

Dalton Trumbo’s words, quoted earlier, seem almost prophetic today, likely seemed prophetic when Trumbo was blacklisted and imprisoned during the Red Scare, and will likely ring with prophecy again in the future.

“It will always be a cause with ideals so high that no mere law can restrain the execution of its judgments. And it will always be based on hatred and fear. To-morrow it may come again.”

The world today is clearly different, and this community is not the leftist enclave it used to be a hundred years ago or the heavily unionized town that it was in 1894 when Grand Junction resisted federal strike breakers and martial law.

Yet, there are still lessons to be learned about how we can resist in the coming years. There is inspiration to be found in the bravery of those who have fought before us, there is a pattern of direct action and civil disobedience to studied, there are precedents of welcoming Japanese-Americans into our community to strive for, and there is a narrative of perseverance, as even anti-socialist suppression and the rise of the KKK could not keep the socialists or their ideas from moving forward.

What will some future historian write about our resistance to MAGA fascism? Will we leave them something to write about? Will some future radical find inspiration in our derring-do, find courage in the stands we make today, or find resolve in our actions in the face of hopelessness?

We hope so.

One thought on “Finding Hope in the Grand Valley’s History of Resistance”