by Jacob Richards

On June 5, from when Deputy Zwinck first pulled over Caroline Dais Goncalves for following too close behind a semi truck, through her release and later arrest by ICE/HSI officers, five separate queries were made of the Grand Junction Police Department’s Motorola Solutions cameras by two Garfield County Sheriff Deputies.

The Goncalves case has made national news after the Colorado Attorney General sued Mesa County Deputy Zwinck for aiding in the arrest of Goncalves by ICE/HSI. Now Mesa County has in turn filed suit against the Governor and the Attorney General.

According to the records obtained by The Revolutionist via a Colorado Open Records Act, Sergeant Brett Borrow and SPEAR Task Force Officer Nate Lagiglia made a total of five requests between 1:36pm when Zwinck first pulled over Goncalves and 2:09pm when HSI reported to the “highway hitters” Signal group chat that they were “Transporting to HSI.”

No reason was given as to why the searches were made or what they were looking for.

But we know a little about Nate Lagiglia. He is known to go out of his way and outside the law to aid ICE, like the next-county-over kind of out of his way.

Nate Lagiglia was the Garfield County Sheriff deputy involved in the arrest of Luis Armando Rivas at the Glenwood Springs Wal-Mart on June 3, which we reported on in the last issue of The Revolutionist.

A viral video showing Lagiglia and another officer in a SPEAR shirt arresting Rivas and placing him into an unmarked vehicle has garnered around 50,000 views on social media.

Lagiglia’s summary states that he aided HSI Special Agent Carter with the arrest of Luis Rivas. He states that he was told that Rivas “was wanted for federal charges.”

In the two months since his arrest, Rivas has not been charged with any crime and did not have an active judicial warrant. His attorney, Hector Gonzalez, of Gypsum, was unaware of any criminal investigation and confirmed that no warrant was executed in his arrest.

Lagiglia also reports being asked to follow Agent Carter to De Beque for “officer safety.” Agent Carter told Lagiglia that they “were meeting with ERO to transfer custody of Luis at the Debeque [sic] Maverick Gas station.”

The Garfield County Sheriff Department is still refusing to release the body camera footage from the June 3 arrest, citing ongoing federal investigation.

The GJPD cameras that Lagiglia accessed are Automatic License Plate Readers (ALPRs).

ALPRs, and specifically the company FLOCK Safety, have garnered the attention of activists in Denver and around the nation in recent months.

“Surveillance systems like this never remain limited to one group. The same technology used to track immigrants today will inevitably be turned on by others tomorrow: patients crossing state lines for abortions, journalists protecting confidential sources, workers organizing for fair labor conditions,” said Karen Orona with Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition, adding “FLOCK erodes constitutional protections for all citizens.”

Women seeking reproductive care in other states have been tracked using ALPRs, and cases of officers caught spying on their estranged ex-wives have come to light in recent months.

“We do collaborate with local, state, and federal law enforcement partners to address serious crimes, the Grand Junction Police Department does not perform camera searches for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), nor do we provide ICE with access to our LPR system,” said Grand Junction Chief of Police Matt Smith in an email to The Revolutionist.

But ICE has repeatedly gained side-door access into these national systems through friendly agencies and officers.

In June, it was revealed that the Loveland Police Department had given an ATF agent access to their FLOCK account. He was conducting searches on behalf of ICE of the entire nation-wide network of FLOCK cameras.

Additionally, 404 Media has reported on the ways that ICE has gained access to local ALPR camera systems thousands of times through friendly local agencies.

Many agencies, like the Denver Police Department, had no idea that ICE was finding ways to access their camera data.

In July, it was revealed that the Denver Police Department’s FLOCK Safety camera data was accessed by outside agencies from around the country 1400 times conducting immigration enforcement related searches before the national sharing function was turned off.

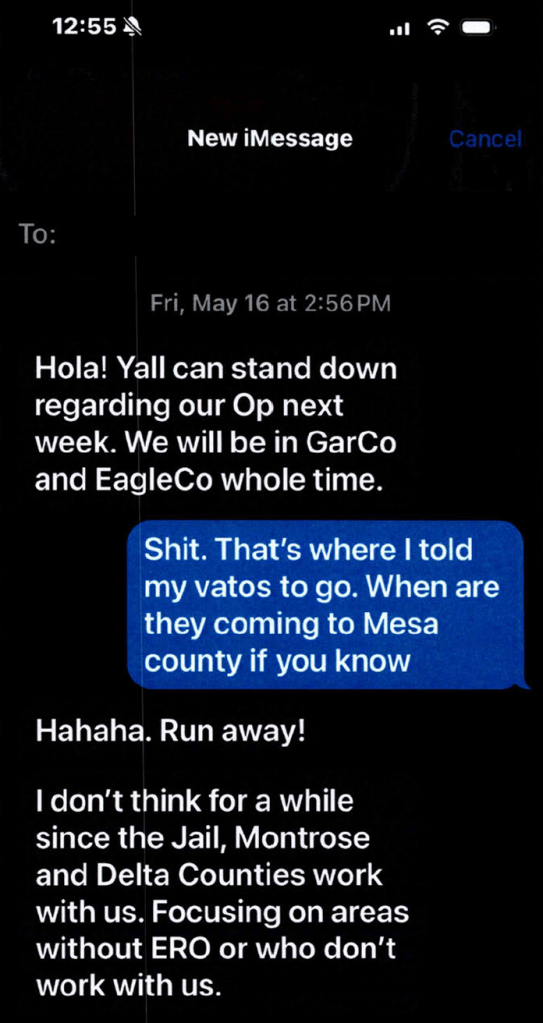

Of local note, a text message buried and unreported in the fallout of the Goncalves case from an unnamed Homeland Security Investigations supervisor indicates that the Mesa County Jail, Montrose, and Delta counties are working with ICE, and should give us pause about sharing camera data even with neighboring jurisdictions.

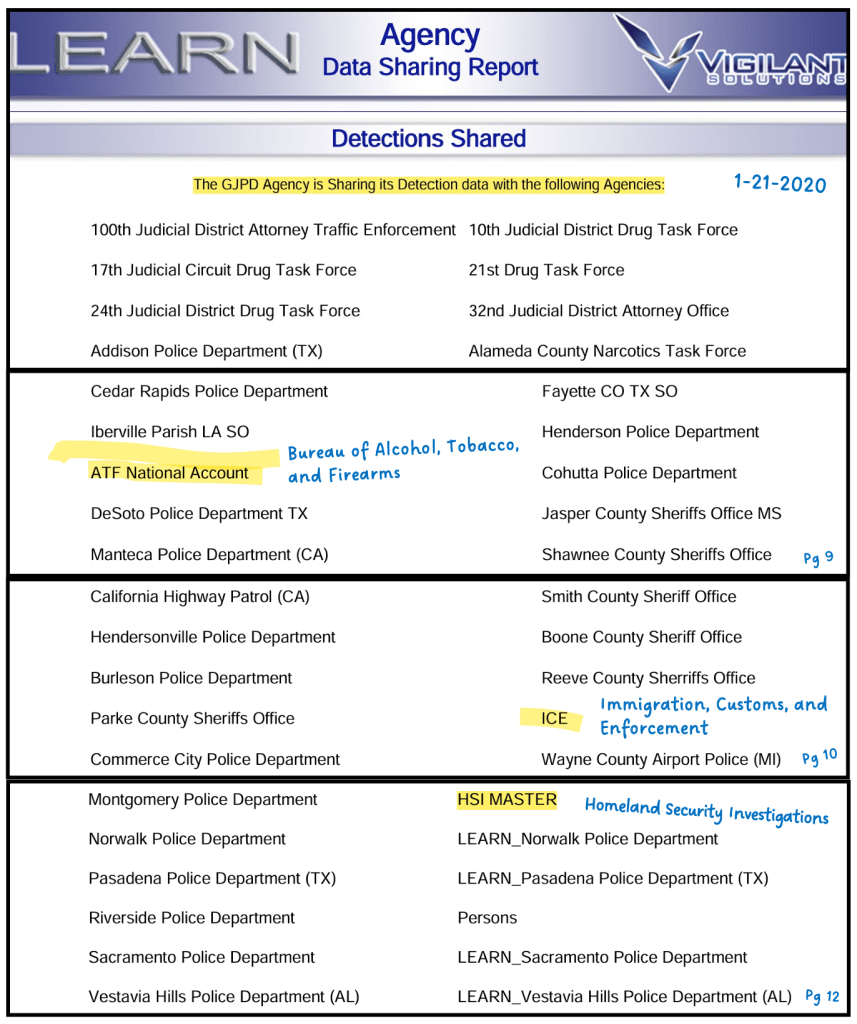

Additionally, in 2019, GJPD cameras were sharing data with immigration enforcement. Documents from Vigilant Solutions (now Motorola Solutions) show that GJPD cameras were sharing data with over 500 outside agencies, including “ATF National account”, ICE, and HSI.

This technology has become omnipresent in the last two decades.

Flock Safety ALPR cameras are in use by over 5000+ local law enforcement agencies nationwide, and are just one of many providers. Motorola Solutions cameras are in over 2500 communities.

These cameras are not like red-light or speeding cameras that only trigger when an infraction is detected; they log every license plate, and that data is being added more and more to mass AI databases.

According to FLOCK, searches for certain bumper stickers are now possible via its “Vehicle Fingerprint” technology.

According to the Grand Junction Police Department, they have a total of 250 cameras, 30 of which are ALPRs. GJPD uses a mix of three providers: FLOCK Safety (as of October 2024), Motorola Solutions, and Project NOLA.

Mesa County Sheriff’s Office has a total of 157 cameras, 15 of which are ALPRs, and has contracts for 11 new FLOCK safety cameras in the near future.

Colorado State Patrol has a total of 68 ALPR cameras. They use Motorola Solutions and Elsag.

Glenwood Springs Police Department, Garfield County Sheriff, Montrose County Sheriff, and Montrose Police Department never responded to our inquiries about the ALPRs they have in use.

Project NOLA, Motorola Solutions, and Elsag have all the same pitfalls and privacy concerns that activists bring up about FLOCK Safety.

Elsag is a division of Leonardo Worldwide, a weapons manufacturer, which also manufactures cameras that are specifically designed for international border crossings. Their website proudly proclaims, “Leonardo works closely with law enforcement and homeland security agencies globally to create customized plate reader solutions for effective and quick policing.”

Project NOLA is more focused on facial recognition and crime cameras, but in New Orleans, where most of their network is, the police are no longer allowed access to their data amid growing privacy and constitutional concerns.

These tech companies and police departments that use them are quick to point to cases where the cameras were pivotal.

FLOCK Safety also puts out pay-to-play quasi-scientific studies that don’t seem to stand up to scrutiny.

Data shows that during 2019, just 26 ALPRs operated by the GJPD scanned 4,860,761 license plates and had less than 100 “hits” for all of 2019.

“Local law enforcement’s partnership with ICE via these databases normalizes unchecked surveillance, disproportionately harming marginalized communities first while ultimately threatening everyone’s rights. When police can retroactively reconstruct 30 days of any person’s movements without oversight, it puts us all in danger. To protect both immigrant families and the freedoms of every Coloradan, we must dismantle this surveillance system,” said Orona.

“There are no state guidelines for the use/deployment of ALPRs,” said Lawrence Pacheco with the Colorado Attorney General’s Office. “The use of ALPRs is a local government issue.”

The deployment of ALPRs without severely restricting the sharing features leaves agencies open to violations, often inadvertently, of Colorado state law which prohibits the sharing of Personally Identifying Information (PII) for the purposes of immigration enforcement.

Without guidance from the Attorney General’s office, local law enforcement agencies are left to navigate the technical, ethical, and legal implications of these rapidly evolving technologies on their own, creating a patchwork of procedures and permissions that can be exploited by HSI and ICE to gain access to data they, under Colorado law, should not be accessing.

We need to secure and watch-dog local law enforcement’s use of these systems, remove them where possible, and demand investigations into the widespread cooperation by local law enforcement in western Colorado with immigration enforcement.

NOTE: writer Jacob Richards recently discussed this story and the Goncalves case, with more angles and more depth at KWSI radio.

###

The Revolutionist is 100% volunteer run and subscriber funded. We do not sell our soul for advertising dollars, nor do we prostrate ourselves for grants from the non-profit industrial complex. We are community media. Join the community! Subscribe today at whatever rate you can, and get a hard copy of The Revolutionist in your mailbox. Subscribing subsidizes free distribution copies.

3 thoughts on “GJPD Cameras Accessed Five Times During Goncalves Incident”