by The People’s History of the Grand Valley

Yep Mow made news when he first arrived in Grand Junction in November of 1882, from Gunnison, via wagon. He opened a laundry, and invested in Grand Junction real estate seeing the potential of this ‘future metropolis.’

Just months before his arrival in Grand Junction, the Chinese Exclusion Act had been signed into law. The act made immigration from China illegal and consigned Chinese people already in America to the status of ‘resident aliens’ without the same basic civil-rights, and blocking any path forward to citizenship.

The lesser-known Page Act, passed back in 1875, effectively barred women of Asian descent from immigrating to the United States. The Page Act coupled with wide-spread Miscegenation Laws, which made interracial relationships illegal, made it almost impossible for Chinese laborers to build families.

Before these two laws, America had an open immigration policy. This is the point that our country became a “papers please” society. It was the starting point in a long arc of history that has led to the ICE raids of today.

These immigration laws were also the beginning of the idea that certain people are illegal, or are criminals. Before these laws, which criminalized people’s mere existence based on race, people were not viewed as criminals, as an identity, but as people who had committed crimes.

Coupled with alcohol and narcotics prohibitions in coming decades was the genesis of our modern idea of ‘criminals.’ And the resulting police state.

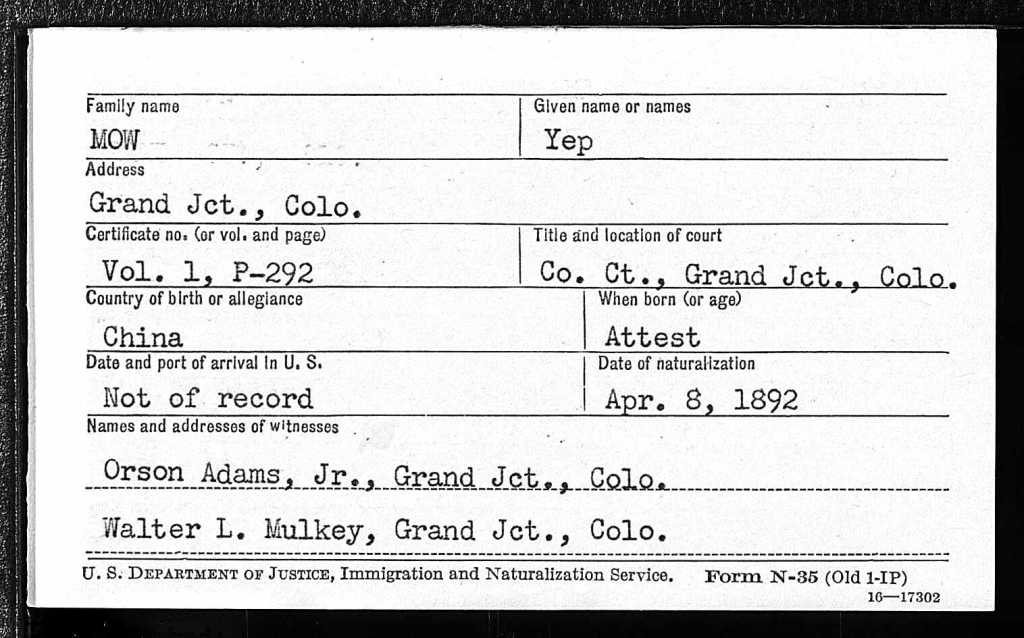

Mow was lucky, and already had his application for citizenship filed before the passing of the Exclusion Act, and would eventually gain citizenship in 1892.

While Yep Mow was the first Chinese immigrant to Grand Junction, Chinese laborers were already at work in Mesa County, building the narrow-gauge railroad that first linked Grand Junction with the outside world.

Archaeological evidence indicates that Chinese laborers worked and lived at the Excelsior station, just east of the Colorado/Utah border.

By August of 1883, encouraged by race-based laws being passed in D.C., motivated by xenophobic labor movement firebrands, and inspired by anti-Chinese race riots around the west, an anti-Chinese agitation started to brew in Grand Junction.

It started with a petition demanding that the railroad quit using Chinese labor in Mesa County, then reports of an opium den spread through town, (later turned out it was run by white citizens), and culminated as a mob organized by a ruffian, and would-be labor organizer, Buck Gilliland, to run Yep Mow, and the one other Chinese laundry owner, Sam Sing out of Grand Junction.

The mob was reportedly given permission by the town Marshal to run the Chinese businessmen out of town, and the mayor was in the mob plying the would-be rioters with booze.

The editors of Grand Junction News, Edwin Price and D.P. Kingsly, refused to let this “most damnable disgrace,” happen in their town. In the columns of their paper they argued against lawlessness, even publishing a letter by early Chinese civil rights leader, Wong Chin Foo, the week before the agitation.

D.P. Kingsly stood out in two roles during these troubles, first as a newspaper man advocating against disorder, and as a captain in the frontier militia.

Sheriff Florida, Captain Kingsly, and the militia guarded Mow’s and Sing’s laundries as well as the armory for four days and prevented this effort to “drive out, kill, or scare the innocent Chinamen and destroy their property.”

Denver’s Rocky Mountain News reported “Grand Junction is having a Chinese agitation of its own. The News is espousing the side of the Mongols with a persistence worthy of a better cause.”

These anti-Chinese race riots and massacres usually had a different ending. In 1880, Denver’s Hop Alley riot cost one man his life and resulted in dozens injured and Denver’s small ‘Chinatown’ burned to the ground. That same year miners in Leadville, dynamited the cabin of the lone Chinese resident of that mining district with him inside. In 1885 in Rock Springs, Wyoming a dispute between Chinese and white miners spilled over into mass violence and at least 28 Chinese miners were killed. 1902 vigilantes drove the Chinese residents of Silverton out of town at the barrel of the gun. Aspen and other mining towns often ran off Chinese laborers as soon as they got off the train..

Both Mow and Sing stayed in the GJ, and by 1892, Yep Mow was one of Grand Junction’s most successful residents.

In 1888, The News reported Mow’s return to the Grand Valley after visiting China for a couple of years and that “Yep made considerable money in Grand Junction in the early day [sic], that he invested in town lots, which are to-day growing valuable.”

G. McAbee, remembered Mow, in a 1957 Letter to the Daily Sentinel: “He was a tall, good-looking Chinese and I think he ran a laundry… he must have made good at it, for he told my brother he was going back to China and marry a ‘little foot’ women.”

When town founder George A. Crawford died in 1892, his estate paid Mow $2.75 for Crawford’s outstanding laundry bill and $5513.45 to repay a $5000 business loan. $5000 in 1892 is equal to $177,498 in today’s money.

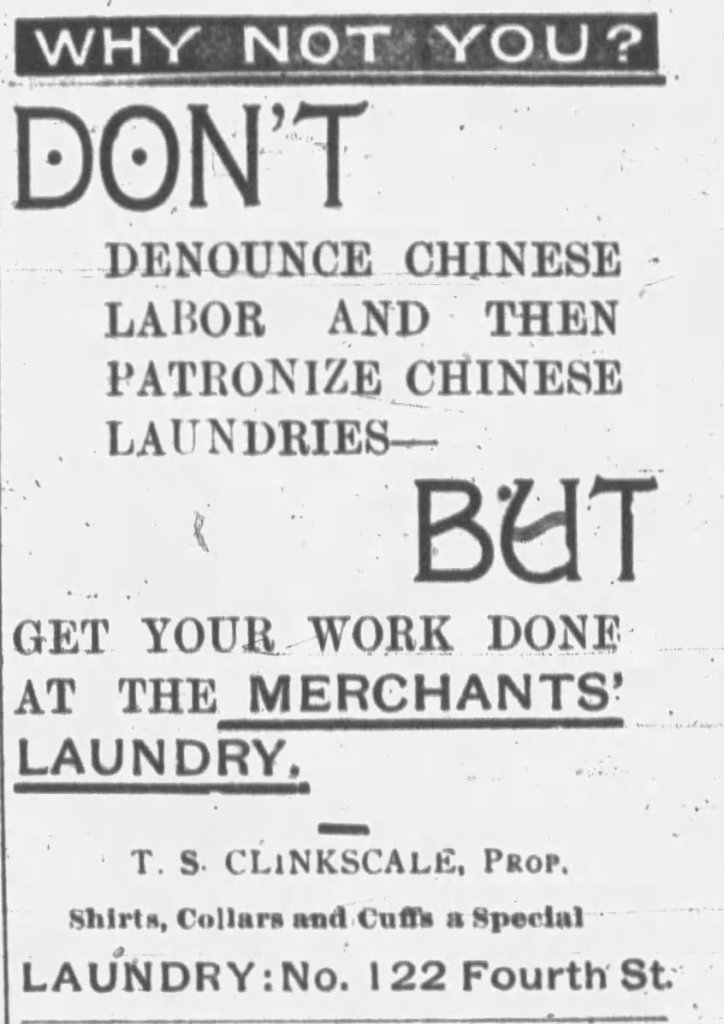

While Mow found opportunity in frontier Grand Junction, Sinophobic attacks punctuate the era. In 1895, Merchants Laundry ran ads in the newspaper encouraging Junctionites “don’t denounce Chinese labor and then patronize Chinese laundries.”

Attacks against Chinese people and their business continued with some regularity until the last Chinese resident, Lee Chong, was assaulted in March of 1921. His business was damaged, and he soon left town.

The Daily Sentinel objected:

“It doesn’t look good for the law enforcement or the law protection facilities of this community when a resident—even though he may be a Chinaman—must be set upon and injured and frightened to such an extent that he leaves town after a long, peaceful and respectable residence here.

More than once this sort of thing has occurred here and the only offense of the victim was embodied in the fact that he was a native of China.”

The Chinese Exclusion Act would eventually be repealed in 1943, but by then a race-based quota system for immigration was firmly in place that favored immigrants from western European countries.

Unable to form families, the Chinese population dwindled and were largely replaced by Japanese laborers, who in turn were herded in internment camps during WWII.

Immigrants today, like Mow, continue to be exceptionally good at starting businesses–willing to perform the hard unpleasant but necessary labor that makes society function. To this day the peaches don’t pick themselves, and the toilets in Aspen are not self-cleaning.

###

The Revolutionist is 100% volunteer run and subscriber funded. We do not sell our soul for advertising dollars, nor do we prostrate ourselves for grants from the non-profit industrial complex. We are community media. Join the community! Subscribe today at whatever rate you can, and get a hard copy of The Revolutionist in your mailbox. Subscribing subsidizes free distribution copies.

One thought on “Yep Mow: GJ’s First Immigrant”