by Jacob Richards

The state killings of Alex Pretti and Renée Good in Minneapolis have not only galvanized a nation and led to widespread protest, general strikes, and student walkouts, but they have also inspired a tidal wave of poetry, music, and art.

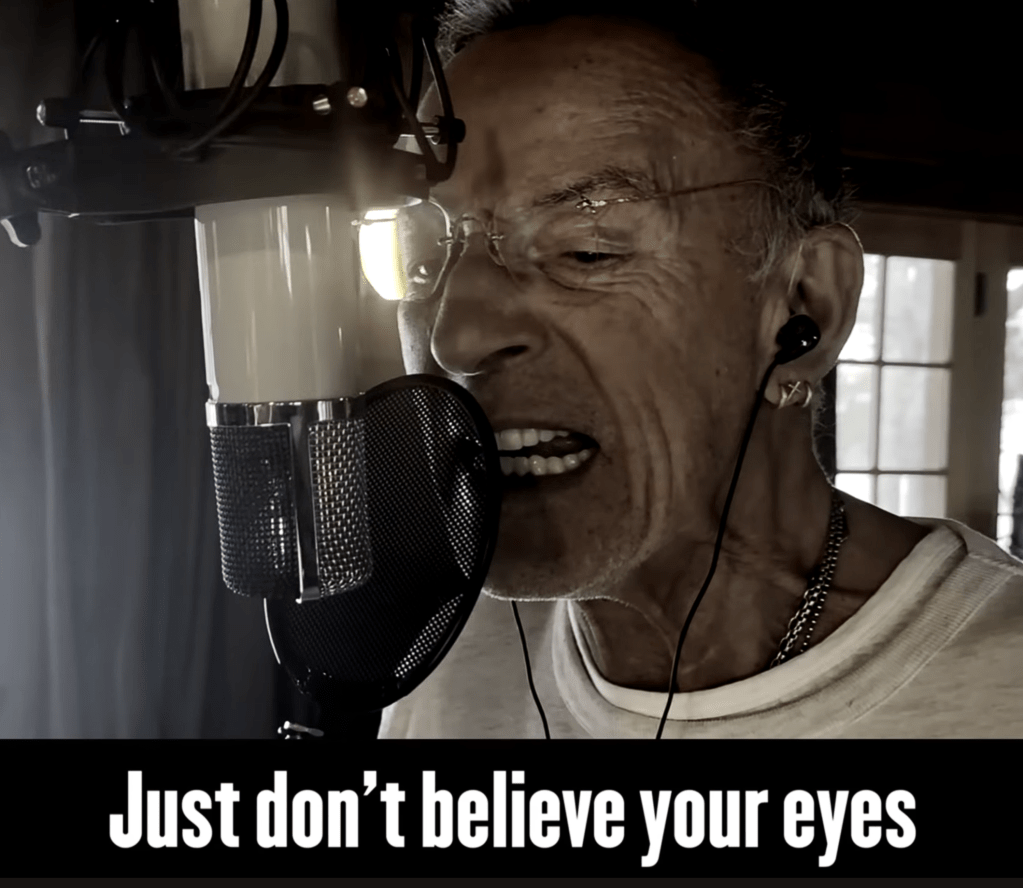

Most prominently, Bruce Springsteen’s “Streets on Minneapolis,” is topping the charts. Its lyrics hark back not just to the “Star Spangled Banner” but also to Minneapolis-born protest-folk legend Bob Dylan.

“Against smoke and rubber bullets

In the dawn’s early light

citizens stood for justice

their voices ringing through the night.”

Springsteen is far from the only songwriter responding to the state violence. In recent days, perennial punk staple NOFX has dropped “Minnesota Nazis.” Country band The Midnight Republic released “Not One More.” Folk-punk protest anthem regular Billy Brag released “City of Heroes.” Dozens of other smaller bands have dropped tracks inspired by the killings of Pretti and Good as well as the city-wide general strike, nationwide protests, and walkouts and disruptions to business as usual.

“Song is a vehicle for us to grieve, it’s a vehicle for us to feel rage, it’s a vehicle for us to strengthen ourselves,” said an unnamed chorist with Singing Resistance in Minneapolis to CNN. They added “that song ‘I’m not afraid’ that I sang, we’re not singing it because we are actually not afraid. Like we are afraid, it is terrifying…and it’s a way to gather our courage.”

Poets, songwriters, and artists have critical roles to play in moments of history like we are living and resisting through today.

Songs and poems memorializing the martyrs of social revolutions punctuate our history dating back to the peasants’ revolt of 1381 in England, at least, if not all the way back to the dawn of story-telling.

Union troops sang and improvised the song “John Brown’s Body” about radical insurrectionary abolitionist John Brown who led a failed uprising at Harper’s Ferry. They sang it marching into the hellfire of the Civil War firing lines and red-hot grapeshot to give themselves both purpose and courage.

Labor songs were sung for courage on the picket lines and have since become timeless: “Which Side Are You On,” “Solidarity Forever,” and even “This Land is My Land,” by Woody Guthrie, despite its colonial baggage, continue to take on new lives and find new relevancy as they cross genres and movements.

During the 1960s, protest and anti-war anthems abounded and often responded to the martyrs and injustices of the day. Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young’s “Ohio” was a response to the killing of four protesters by the National Guard at Kent State, and “Fortunate Son” was written in a 20-minute rage by John Fogerty after he read an article about a senator’s son weasling out of the Vietnam draft.

Black liberation and Civil Rights martyrs Fred Hampton, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. still get regularly name-dropped on hip-hop tracks.

Some of this seems like ancient history, but Trump is ancient, and his wealth started somewhere. In fact, there’s a folk song about it.

Prolific folk musician and communist Woody Guthrie’s archives contain an song titled “Old Man Trump.” The song is about Fred Trump, the bastard landlord that gave Donald a billion dollars as a birthright — a billion made on the backs of the poor and the taxpayer.

“I suppose that Old Man Trump knows just how much racial hate

He stirred up in that bloodpot of human hearts

When he drawed that color line

Here at his Beach Haven family project

…

Beach Haven is Trump’s Tower

Where no black folks come to roam,

No, no, Old Man Trump!

Old Beach Haven ain’t my home!”

Far too often, the poets, the writers, and the songwriters are the ones we end up memorializing when they, too, are killed or repressed by the state.

Renée Good was a poet. In 2020, she won awards for her poem “On Learning to Dissect Fetal Pigs,” which deals with her conflicts between faith and science:

“it’s the ruler by which i reduce all things now; hard-edged & splintering from knowledge that

used to sit, a cloth against fevered forehead.”

Finding her poem has become difficult because the thousands of lines of verse that have sought to make sense of her violent death, remember her life, honor her sacrifice, and/or rally our collective spirits for the fight ahead have proliferated and multiplied on the internet.

It’s like poets and creatives instinctively understood what Michael Franti meant when he sang after the infamous 1999 Battle in Seattle:

“I’m a little under the weather today,

too much pepper spray can make a brother congested.

You know what I’m saying,

but the harder they hit us the louder we become

like the skin of a drum,”

There are some sources that indicate that Alex Pretti was also a poet or writer at some level, and it begs the question: Why are artists always at the forefront of movements for change?

A snippet of dialogue from Puerto Rican poet and novelist Giannina Braschi’s book, Ya Ya Boing!, sums it up.

“Poets and anarchists are always the first to go./ Where./ To the frontline. Wherever it is.”

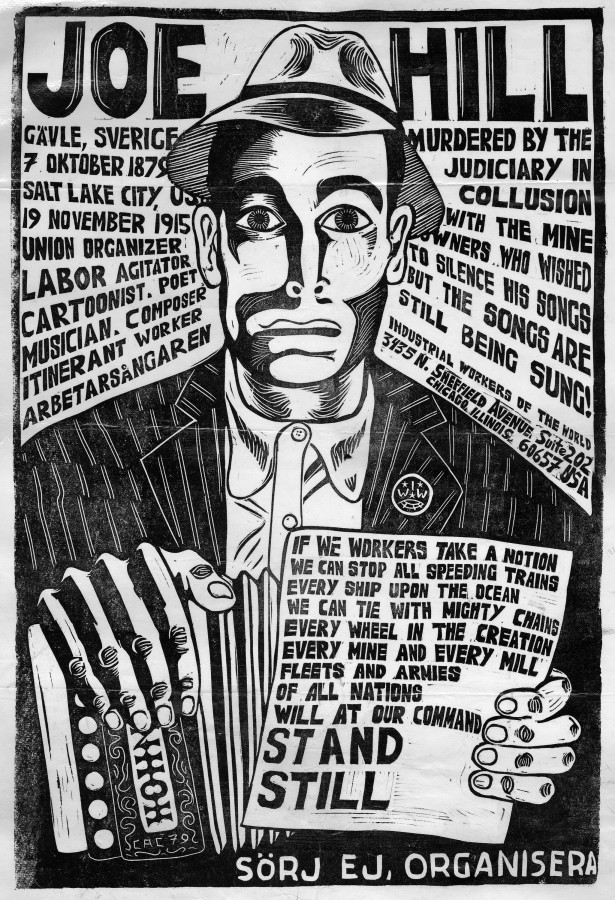

This was famously true with Joe Hill, a radical labor organizer, songwriter, and Wobblie. Hill was a Swedish immigrant and prolific song writer with the Industrial Workers of the World in the 1900s and 1910s.

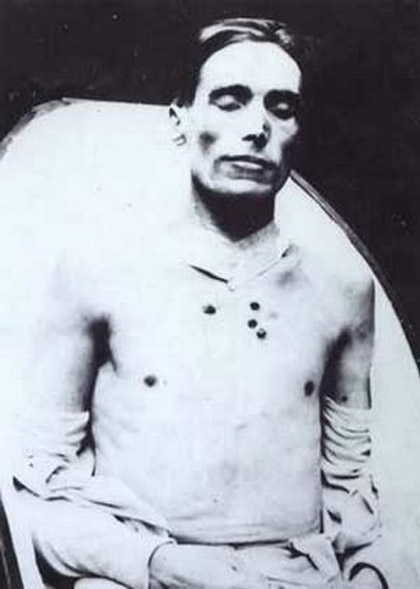

Hill was framed for a murder in Salt Lake City, Utah, and was martyred by the state in 1915. The conviction is widely considered illegitimate. Hill’s only crime was being a well-known Wobblie songwriter in the wrong jurisdiction.

One of his last communications was to labor legend Big Bill Haywood, and it ended, ”Don’t waste any time mourning. Organize!” The line can still be found on posters, T-shirts, and in song lyrics.

Hill’s last poem, titled “My Last Will,” was sent out of the prison just hours before his bloody execution by firing squad. It reads:

My Will is easy to decide,

For there is nothing To divide

My kin don’t need to fuss and moan—

“Moss does not cling to a rolling stone”

My body? — Oh! — If I could choose

I would want to ashes it reduce,

And let The merry breezes blow

My dust to where some flowers grow

Perhaps some fading flower then

Would come to life and bloom again

This is my Last and Final Will. —

Good Luck to All of you.

At Hill’s well-attended funeral, former Grand Junction bookstore owner, Wobblie, and socialist George Falconer sang:

“Long-haired preachers come out every night

Try to tell you what’s wrong and what’s right

But when asked about something to eat

They will answer with voices so sweet:

You will eat (You will eat) bye and bye (Bye and bye)

In that glorious land above the sky (Way up high)”

The lines are from Hill’s song “The Preacher and the Slave.”

Pat Robenson in the 1930s, Phil Oches in the 1960s, and Joan Baez in the ’70s and ’80s have since made the “Ballad of Joe Hill” a testament to fearlessness in the face of oppression and bravery in the face of death.

Today, yet again, the poets are becoming the martyrs and fodder for both verse and action.

The deaths of Pretti and Good, as well as the example of resistance being set by the citizens of Minneapolis, are more than worthy of being commemorated in verse and sung at lines of riot police through bullhorns.

The people have responded with Joe Hill’s fearlessness while becoming louder like Franti advised, and have shown up in the same ways Renée Good and Alex Pretti did for their community.

The people are responding like poets — hearts heavy with emotion, mouths full of chants and full-throated denunciations, fists full of keyboards, pencils, and picket signs.

The fearlessness of the American people can best be seen in the videos of the recent killings. In these videos, you see people from all walks of life not taking cover — not running away, not turning away, not remaining silent, but instead filming, running fearlessly toward the violence to help, to document, to demand justice.

As a nation, we are witnessing daily emperor-wears-no-clothes moments. Moments where we are asked to believe the regime and their media instead of our own eyes and hearts. The contradiction it creates is something ripe that inspires both resistance and art.

These are the rare moments in history where the veil can be pierced, the illusion can be shattered, where we can glimpse behind the curtains, and our best tool is always our creativity — both in verse and art but especially in the streets.

These are the moments that demand sharp words and decisive collective action.

Can you feel it too? The ground swelling? As if the killings of Renée Good and Alex Pretti have awoken something great and immeasurable, something that Percy Bysshe Shelly spoke to in his 1819 poem “The Masque of Anarchy.”

The poem, penned after the Peterloo Massacre, in which 18 peaceful protesters were killed and 400 to 700 more were wounded by the king’s soldiers, is seen by many literary and political scholars as the first modern articulation of the idea of nonviolent resistance. It ends triumphantly:

“Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number,

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you —

Ye are many — they are few.”

###

The Revolutionist is 100% volunteer run and subscriber funded. We do not sell our soul for advertising dollars, nor do we prostrate ourselves for grants from the non-profit industrial complex. We are community media. Join the community! Subscribe today at whatever rate you can and get a hard copy of The Revolutionist in your mailbox. Subscribing subsidizes free distribution copies.